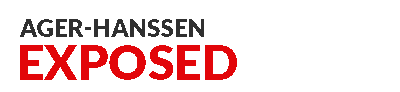

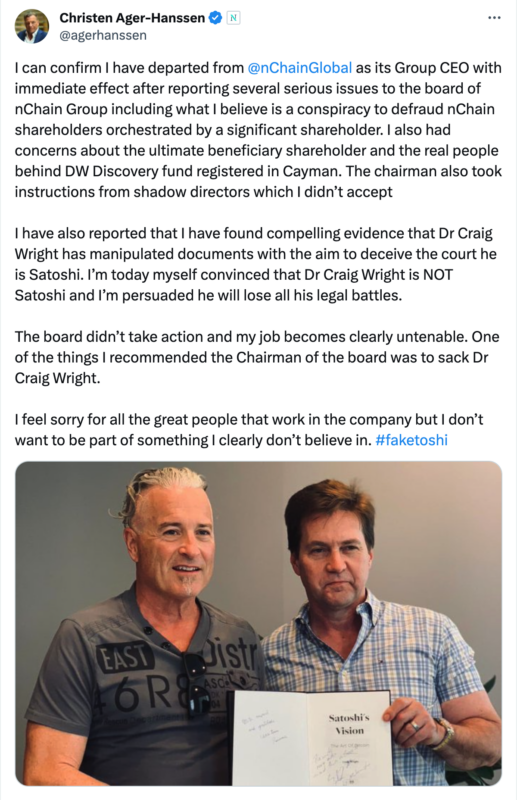

When Christen Ager-Hanssen was fired from his job as the CEO of crypto company n-Chain, he went on a rampage, claiming he was fired for blowing the whistle on alleged business practices of the company’s largest shareholder, Calvin Ayre. In the days following the acrimonious breakup, Ager-Hanssen tweeted incessantly claiming he was fired for ‘blowing the whistle’

While this may have come as a surprise to those who have followed the drama surrounding N-Chain and it’s chief scientist, the self-proclaimed inventor of Bitcoin Craig Wright (and his various court cases in which he was accused of forging documents) in which Ager-Hanssen vociferously defended him for months, it came as no surprise to those who know Christen Ager-Hanssen and his modus operandi.

Believe it or not, nChain is not the first company Christen had failed to take over, before throwing a tantrum and turning on his business partners.

When Christen’s first company, Cognition, failed in the early 2000’s, Christen pulled the exact same stunt against the company’s largest creditor, which led to Ager-Hanssen being declared bankrupt and the former partner being imprisoned for tax fraud.

Started in 1997, Ager-Hanssen wished to emulate the success of Jan Stenbeck, a Sweish financier who was the chairman of the renowned investment firm Kinnevik where he worked as an executive. He began by ‘buying’ one of Kinnevik’s investments, NetSys, which was a reseller of licenses of Canadian tech company OpenText’s software for NOK 50 million. Christen would claim in Cognition pitch documents that he founded NetSys, which is a provable lie.

The only problem, was Christen did not have NOK 50 million to purchase the company. He managed to convince his friend who worked at the Swedish Pension Fund it was the perfect investment, and had them stump up the entire NOK 50 million in return for a 10% stake in Cognition.

In early 2000, Ager-Hanssen began spreading fake news about his net worth, which no serious journalist believed, as it would mean the story of such a meteoric rise to success entirely passed them by.

His image began to change following the publication of an article appeared in Swedish tabloid newspaper Aftonbladet entitled ‘Richer than Røkke‘, a fantasy puff piece which claimed Ager-Hanssen was “much richer than Kjell Inge Røkke” who was widely regarded for years as legitimately being Norway’s richest man.

Norwegian investigative journalists Ingun Stray Spetalen and Gøran Skaalmo claimed in a 2011 investigation that Ager-Hanssen had sent private investigators to dig into journalists who were planning to write negative things about him and his companies, and used the kompromat uncovered in order to spike any potential negative story. They themselves claimed “we think we were generous when we estimated the entire company to own values of around NOK 250-400 million.” [GBP £18-30 million].

The pair also detail how Cognition’s portfolio worked the same way as Christen’s offer to unsuspecting businesses today: An upfront lump-sum in return for a large stake in the company.

This is then used to grossly inflate the value of the company – for example, if a company sells 10% of its shares for £1 each, the whole company would be estimated to be valued £100. If each share was bought for £10 each, the company would be valued at £1,000 etc.. etc…

Some of Cognitions ‘investments’ appear to have been shelf companies, such as Grundstenen 08442 AB, which made it difficult to understand their provenance or true value.

Using this fake inflated valuation, Ager-Hanssen was allegedly able to convince HSBC Cognition’s portfolio was worth £1 billion (or NOK 20 billion). According to Swedish journalists, nobody has been able to retrieve a copy of this alleged valuation, and Ager-Hanssen has himself refused to send copies to journalists who have enquired.

Despite his alleged status as one of Norway’s richest men, claiming to have two Ferrari’s and a private jet, Ager-Hanssen was also at this time being pursued by accountancy firm Robson Rhodes by Cognition staff who had not been paid for several months.

Because of the fake news Ager-Hanssen was spreading, he attracted the attention of Norwegian investor Hakon Korsgaard, who wanted to invest £25 million into Cognition in return for 105,460 B shares.

Korsgaard’s condition was that Cognition would be floated on the London Stock Exchange and if it were not, Ager-Hanssen would be obligated to buy the shares back himself.

As bad luck would have it, there was an unusual incident with the transfer of millions of pounds related to a Barclay’s bank account. In Ager-Hanssen’s version of events, the bank erroneously deposited £15 million in his account, which he believed to be an incoming payment from Korsgaard. Christen subsequently spent £4 million of this money on Cognition related investments. In Christen’s version of events, when the bank realised their error, they reversed the transaction, leaving him £4 million overdrawn (oddly suggesting his balance was £0 prior to the transaction).

Others whom have looked into the saga claim Barclays realised the payment had somehow managed to leave Christen’s account via a loophole they had not patched, despite him not having sufficient funds, and could not reverse the transaction themselves. In Barclays version of events, Christen promised to repay the money, but when the money did not show up, despite repeated reminders and debt collectors visiting his known addresses, the bank launched legal action against him.

Christen claimed he believed the money had come from Korsgaard, despite the fact the initial deal was for £4 million, not £15, with an additional £21 million due by the end of the year. Korsgaard, pitying Ager-Hanssen, agreed to front him the £4 million liability.

After transferring around of £6.4 million, Korsgaard realised he had been defrauded, and that Cognition’s so-called ‘valuation’ was fraudulently pumped by Christen himself and that the shares were worth far less than he believed, which is likely why Ager-Hanssen kept delaying the floatation on the London Stock Exchange.

Korsgaard initiated legal proceedings and was able to secure a freezing order against Christen’s cars, bolt hole in Blindleia and his London flat. Ager-Hanssen launched a counter-suit, claiming he was owed money and that Korsgaard only reneged on their deal as the ‘dotcom bubble’ had burst.

The litigation dragged on for almost a year, with Ager-Hanssen eventually teaming up with another individual who had been in litigation against Korsgaard, Knut Axel Ugland, who funded the litigation (as Ager-Hanssen had no money to pay his lawyers according to court filings) in return for a cut of any winnings.

Ager-Hanssen did not fight Korsgaard conventionally, as he had no real case, he instead decided to report Korsgaard to Økokrim, the Norwegian financial crime police. Økokrim spent several years turning over every stone in Korsgaard’s financial life, before ruling that some of the money used to fund his investments had been made incorrectly.

The prosecutor Petter Nordeng said at the time: “We will not be accused of following Ager-Hanssen’s path, but we found objective evidence in some of what he pointed out.”

But, as the saying goes, if you lie with dogs you get fleas and after a dispute with Ugland, Ager-Hanssen teamed back up with Korsgaard in order to attack his former partner. During this second round of litigation, Ager-Hanssen was accused by Ugland’s lawyer of extortion and witness tampering. A contemporaneous report also claims Ugland was secretly recorded in his meetings with Christen, which he then deployed in order to discredit him (in the same way he did with Kyle Roche).

A news article from the time claimed Ager-Hanssen had approached Ugland’s finance director, Jan Erik Tønnessen, outside his home at midnight. Tønnessen claims he was threatened and blackmailed, with Ager-Hanssen telling him: “I had to cooperate. If not, he would sell the tape recordings”

In a report from a journalist who attended the court hearings, Ager-Hanssen approached Ugland telling them he wanted to help them in their case against Korsgaard, while he actually had already entered an agreement with Korsgaard to help in the case, which would net him SEK 12 million if he was successful.

In court, Christen said of the undercover recordings: “I would not be believed if I could not document what had been said.” Exactly what he said when he released recordings of nChain boss Stefan Matthews…

More to follow…

If you have found this article useful, please share it on social media.